Deep Dive into Variables in Go

How Go Stores, Names, and Manages the Data You Work With

“Programming is about turning thoughts into instructions. Variables are the containers that let your ideas take shape.”

I still remember my first week writing Go at a real job. I pushed a change that passed every unit test, sailed through code review, and then immediately crashed the moment it hit real traffic. The reason was embarrassingly simple. I misunderstood how a variable was being initialized inside a request handler. That moment taught me something important. Go’s variable rules look simple but they carry design choices that shape how your programs behave in memory, in concurrency, and under load. Once I learned the deeper model, everything clicked. This article gives you that same foundation.

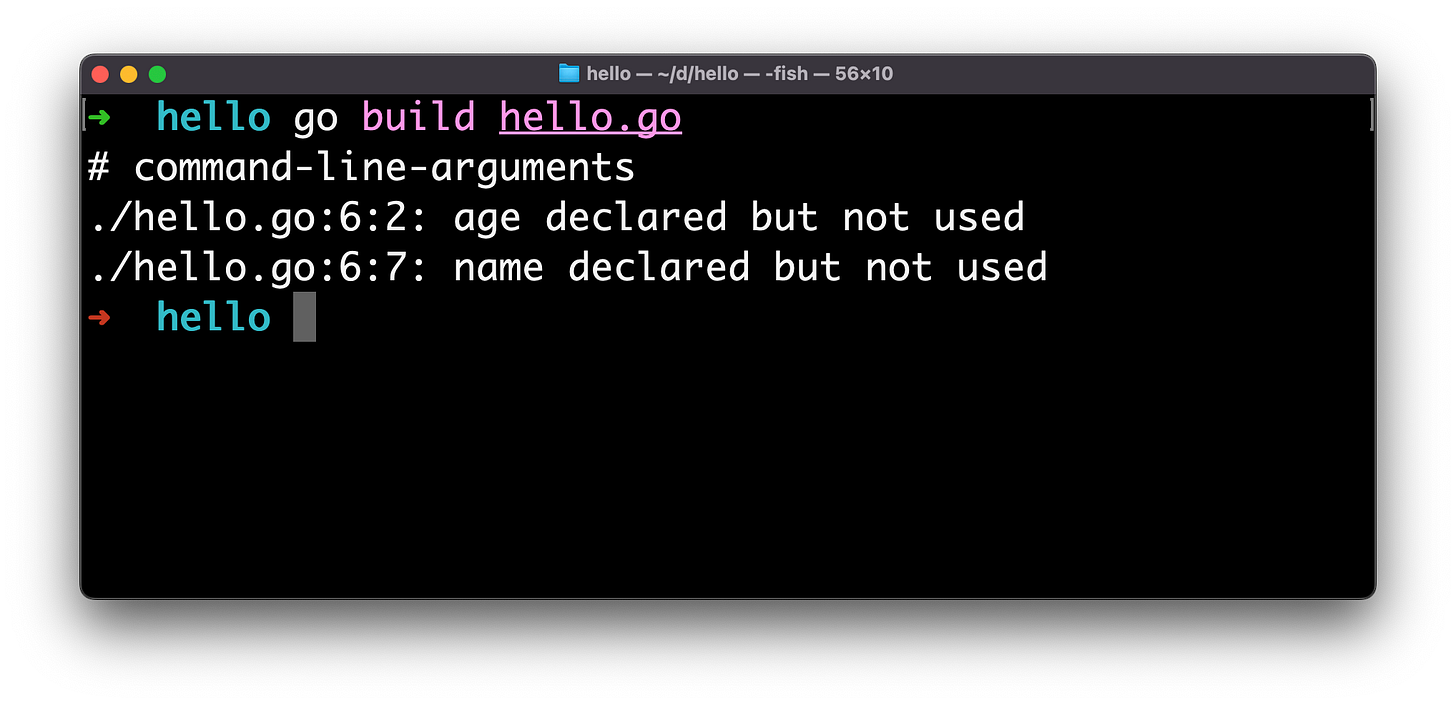

In Go, a variable or imported package that is declared but not used will result in a compilation error. This is a deliberate design choice in Go to promote clean code and prevent potential issues in large projects.

What a Variable Really Is in Go

A variable in Go is a named location in memory that holds a value of a specific type. Go is a statically typed language, so every variable has a type that is known at compile time. This gives the compiler the ability to optimize, catch mistakes early, and generate efficient machine code.

Note. A statically typed language is one where a variable’s data type (like number, text, etc.) is checked and fixed at compile time, before the program runs, meaning you often declare types (e.g.,

int num = 5;), and the compiler catches errors if you try to use a variable with the wrong type, catching bugs early for more robust, optimized code. Languages like Java, C++, C#, Go, and Rust are examples, contrasting with dynamically typed languages (Python, JavaScript) where types are checked at runtime and can change.

In Go, variables can live on the stack or the heap. The compiler decides where they go based on escape analysis. You do not manually pick the storage location, but understanding that this decision exists helps explain why passing values around can allocate memory or trigger later garbage collection.

Three Main Ways to Declare Variables

Go gives you a few different forms of variable declarations, each with a specific purpose.

1. The var Keyword

This is the standard way to declare a variable when you want to specify the type or when the value will be assigned later.

var count int

var message stringYou can also initialize the variable immediately (combine declaration and initialization).

var score int = 42The type can be inferred.

var z = 30 // z becomes intYou can declare multiple variables in one line:

var a, b string = “hello”, “world”Use var when:

you need the zero value

you are outside a function (short declaration not allowed)

clarity matters

2. Short Declaration

This is Go’s compact and idiomatic form, available only inside functions. It declares and initializes a variable at the same time.

name := “David”

total := 100Go infers the type automatically.

Short declarations must declare at least one new variable:

x := 10

x := 20 // invalid, x already existsBut updating some and creating others is allowed:

x, y := 10, 20 // both new

x, z := 30, 40 // x reused, z newUse := when:

you want concise code

you are inside a function

the type is obvious from context

3. Using const for Immutable Values

const Pi = 3.14159

const Name string = “Go”Constants must be compile time values. No function calls, no runtime computation.

Zero Values and Why They Matter

Go does not leave memory uninitialized. Every variable receives a zero value. This is a design choice that removes an entire class of bugs.

Some common zero values:

int → 0

float → 0.0

string → “”

bool → false

pointer, map, slice, channel, function → nil

Zero values matter because your code can safely use variables immediately without worrying about garbage data left from previous operations.

Example:

var count int // count is 0

var name string // name is “”This eliminates uninitialized memory bugs.

Pointers and Variables

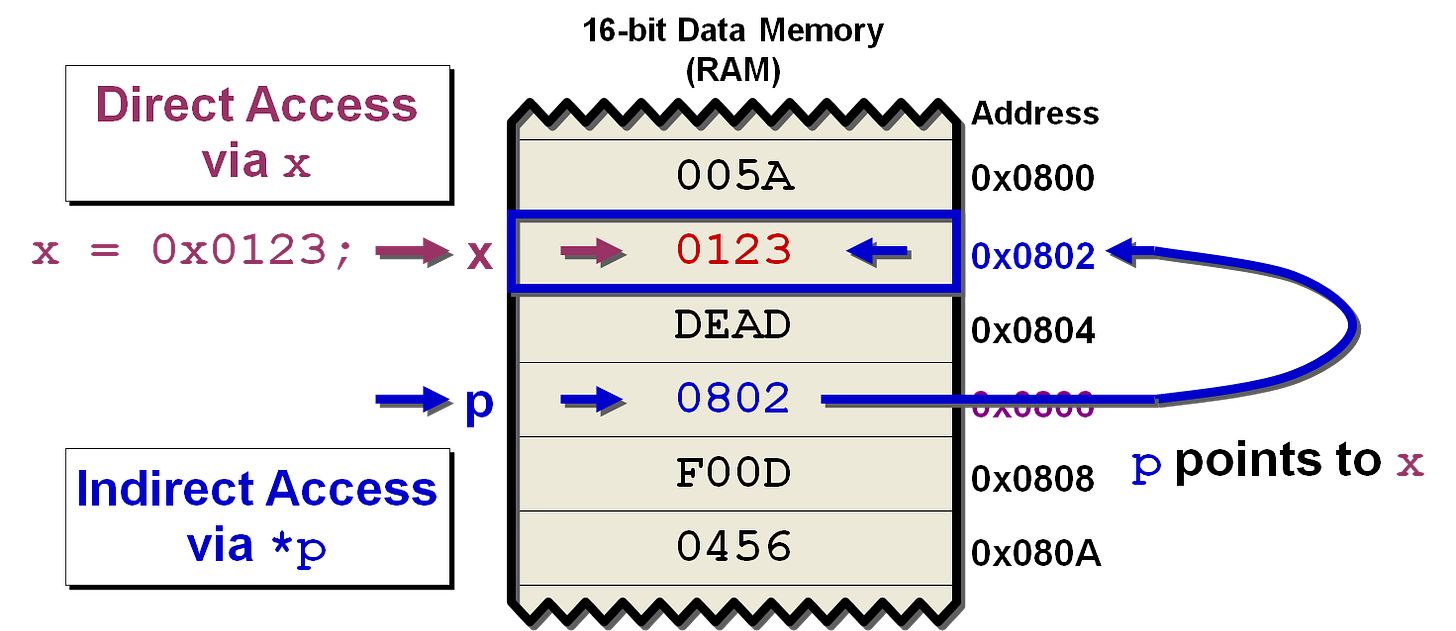

Go supports pointers but not pointer arithmetic. A pointer holds the address of another variable. When you pass a pointer to a function, the function can modify the original value.

value := 10

ptr := &value

*ptr = 20After this, value becomes 20.

Pointers are also part of Go’s escape analysis. If the compiler thinks a variable must outlive the function where it was created, it places the variable on the heap and returns a pointer to it.

Variable Scope

Scope describes where a variable is accessible.

Package Level

Declared outside any function:

var globalMessage = “hello”Visible to all files in the same package.

Function Level

Declared inside a function, visible only there.

func main() {

msg := “inside”

}Block Level

Declared inside braces:

if true {

n := 10

}Shadowing (and Why It Can Bite You)

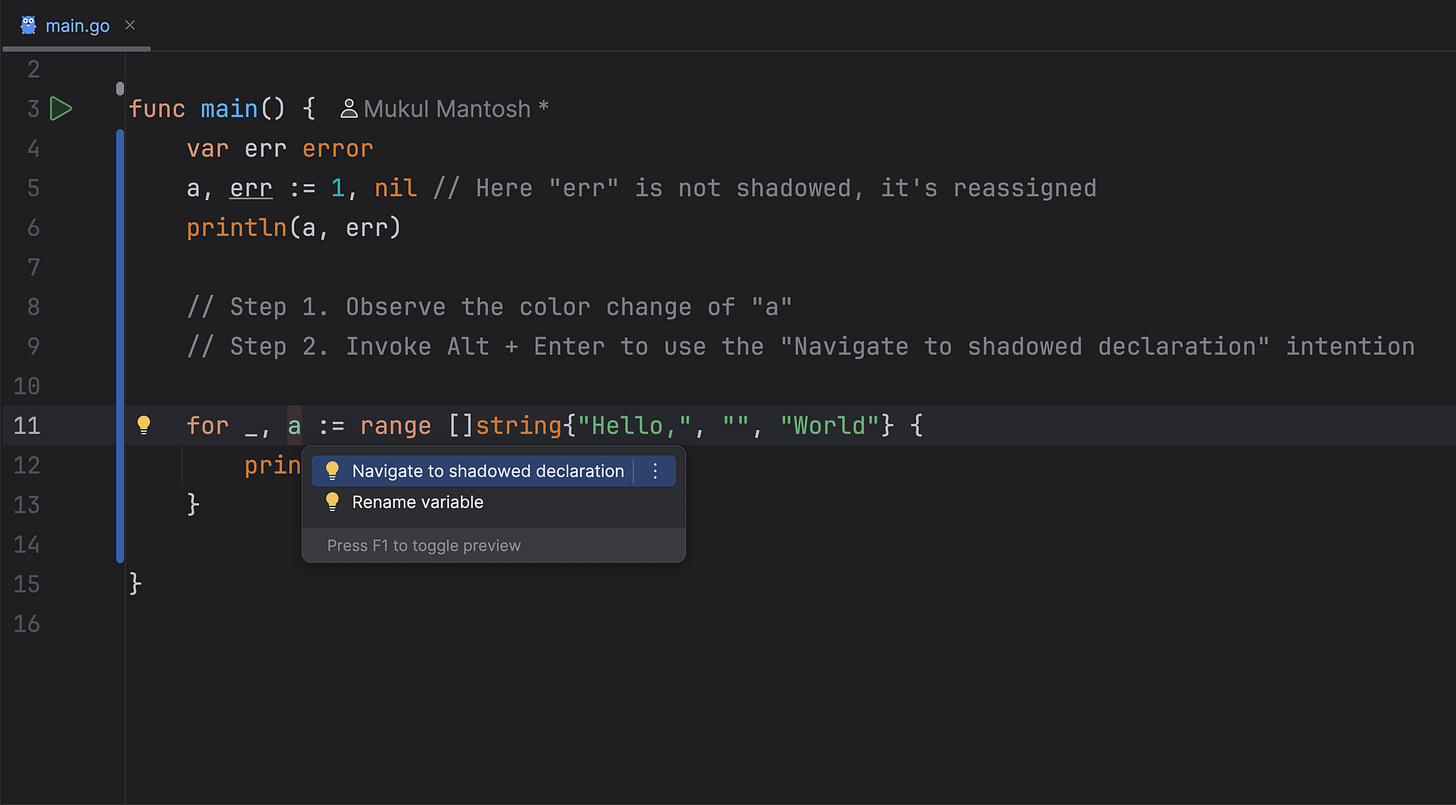

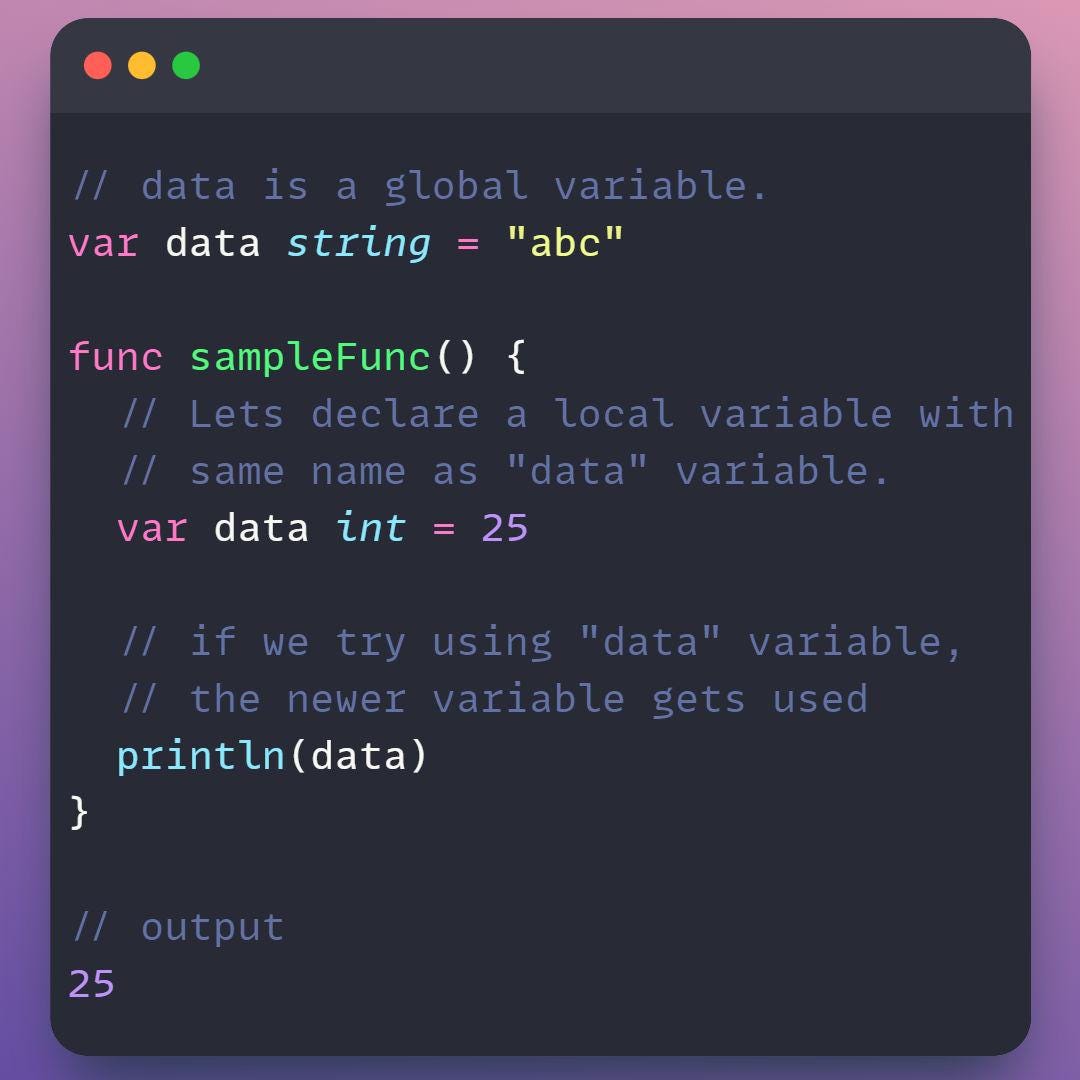

Variable shadowing occurs when an inner block declares a variable with the same name as an outer block. This often happens with the short declaration operator.

count := 10

if true {

count := 20 // shadows the outer count

fmt.Println(count)

}

fmt.Println(count)The first print shows 20 and the second shows 10. This is a classic source of subtle bugs in Go. When in doubt, avoid using the same names in nested scopes.

Constants Are Not Variables

Constants in Go use the const keyword. They behave differently and cannot be modified.

const Pi = 3.14159Constants must be able to be computed at compile time and do not live in memory the way variables do.

How Go Chooses Between Stack and Heap

Although you cannot explicitly choose where a variable lives, the compiler inspects your code to decide.

General rules.

If a variable never escapes its function, Go keeps it on the stack.

If a variable must exist after the function returns, Go moves it to the heap.

func makeValue() *int {

v := 10

return &v // escapes to heap

}Stack variables are faster, so understanding this helps you write more performance friendly Go.

Stack is for temporary, local data that has a clear, defined lifetime within a function. Heap is for data that needs to persist longer or has a dynamic size, requiring the Go runtime’s garbage collector for management.

Using new and make

These allocate different kinds of values:

new

Allocates memory for a type and returns a pointer to the zero value.

p := new(int) // *int pointing to 0make

Works only for slices, maps, and channels, because these need initialization of internal structures.

s := make([]int, 10)

m := make(map[string]int)

c := make(chan int)Summary

Use

varwhen you need clarity or zero value.Use

:=for concise declarations inside functions.Use

constfor immutable compile time values.Zero values make Go memory safe and predictable.

Scope rules determine where variables exist.

Pointers allow reference semantics* without unsafe operations.

newallocates plain types,makeallocates built in reference types.

* Value Semantics. Prefer for small, immutable data structures, or when you need independent copies and want to avoid unexpected side effects from modifications. Pointer Semantics. Use for larger data structures to avoid costly copying, when you need to share and modify data across different parts of your program, or when implementing interfaces that require pointer receivers.

Putting It All Together

Variables in Go look simple at first glance, but they connect directly to the compiler, memory layout, function boundaries, concurrency behavior, and garbage collection. Once you understand how they work behind the scenes, your code becomes clearer and more predictable. More importantly, you avoid the silent bugs that sneak in when you misunderstand how a value is stored, passed, shadowed, or escaped.

“Go’s variable rules look simple but they carry design choices that shape how your programs behave in memory, in concurrency, and under load”

very well said! this article does well to explain the foundation. truly a gem 😖