epoll and kqueue: How Operating Systems Learned to Wait Efficiently

The quiet machinery behind scalable I/O

“The hardest part of I/O isn’t reading data. It’s knowing when to stop waiting.”

Every high-performance server eventually runs into the same problem: waiting. Not waiting for CPU, not waiting for memory, but waiting for the outside world. Network sockets sit idle. File descriptors stall. Thousands of connections exist, but only a few are active at any given moment.

Early operating systems handled this poorly. Modern systems do not—largely because of mechanisms like epoll on Linux and kqueue on BSD-based systems. These APIs fundamentally changed how software waits for I/O, making today’s highly concurrent servers possible.

The problem: waiting doesn’t scale

At a low level, I/O is blocking. You ask the kernel to read from a socket, and if no data is available, the kernel waits. If you have one connection, this is fine. If you have ten thousand, it’s disastrous.

The naive solution is one thread per connection. Each thread blocks independently. This works until thread creation, context switching, and memory overhead overwhelm the system.

The second attempt was polling.

Why select and poll weren’t enough

Early Unix systems introduced select and later poll as ways to wait on multiple file descriptors at once.

Conceptually, they work like this: you give the kernel a list of file descriptors and ask, “Which of these are ready?” The kernel scans the list and tells you.

That scan is the problem.

Each call requires iterating over every file descriptor, even if only one is active. As the number of connections grows, the cost grows linearly. At scale, most of your CPU time is spent asking the kernel the same question over and over again.

The real issue wasn’t that waiting was slow—it was that checking was expensive.

The core insight behind epoll and kqueue

epoll and kqueue are built around a simple but powerful idea:

don’t repeatedly ask the kernel what you care about—tell it once, and let it notify you.

Instead of passing a full list of file descriptors every time you want to wait, you register your interest once. After that, the kernel tracks readiness internally and wakes you up only when something changes.

Waiting becomes proportional to activity, not capacity.

epoll: Linux’s event notification system

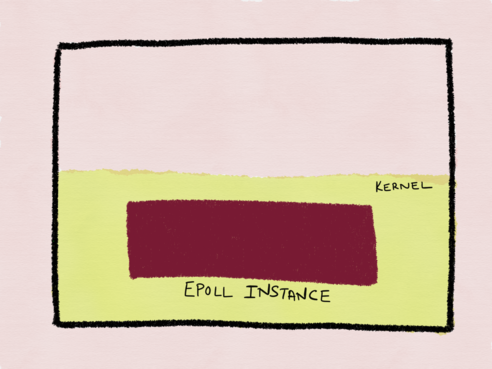

On Linux, this idea is implemented as epoll.

epoll introduces a persistent kernel object called an epoll instance. You create it once, then register file descriptors along with the events you care about—readability, writability, errors, and so on.

int epfd = epoll_create1(0);

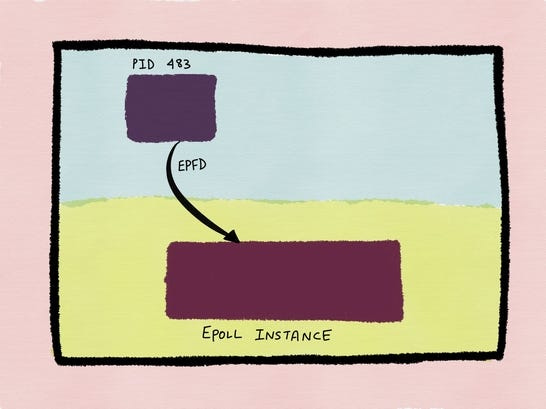

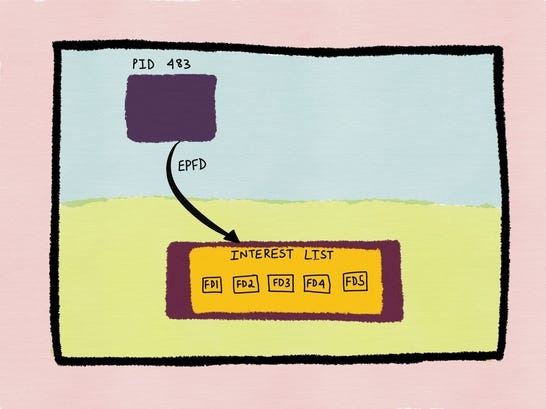

epoll_ctl(epfd, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, fd, &event);This code creates an epoll instance inside the kernel and registers a file descriptor with it. From this point forward, the kernel is responsible for tracking when fd becomes readable, writable, or encounters an error. Crucially, you no longer need to pass fd back to the kernel every time you want to wait—it’s remembered.

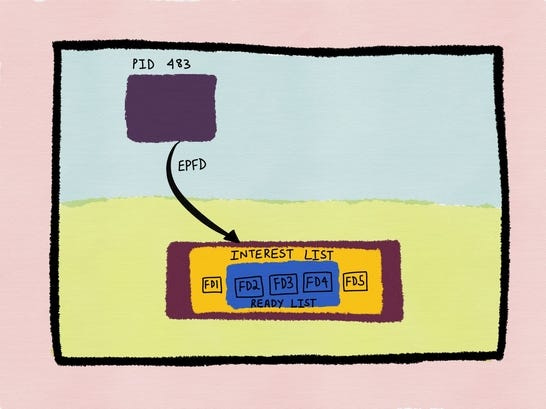

The epoll_create system call returns a file descriptor to the newly created epoll kernel data structure. The calling process can then use this file descriptor to add, remove or modify other file descriptors it wants to monitor for I/O to the epoll instance.

In the above diagram, process 483 has registered file descriptors fd1, fd2, fd3, fd4 and fd5 with the epoll instance. This is the interest list or the epoll set of that particular epoll instance. Subsequently, when any of the file descriptors registered become ready for I/O, then they are considered to be in the ready list.

The ready list is a subset of the interest list.

Method signature

#include <sys/epoll.h>

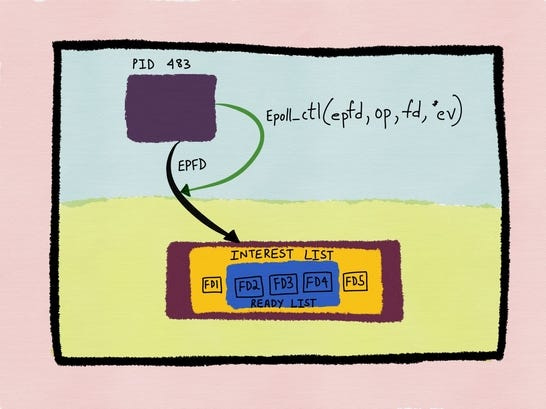

int epoll_ctl(int epfd, int op, int fd, struct epoll_event *event);epfd — is the file descriptor returned by epoll_create which identifies the epoll instance in the kernel.

fd — is the file descriptor we want to add to the epoll list/interest list.

op — refers to the operation to be performed on the file descriptor fd. In general, three operations are supported:

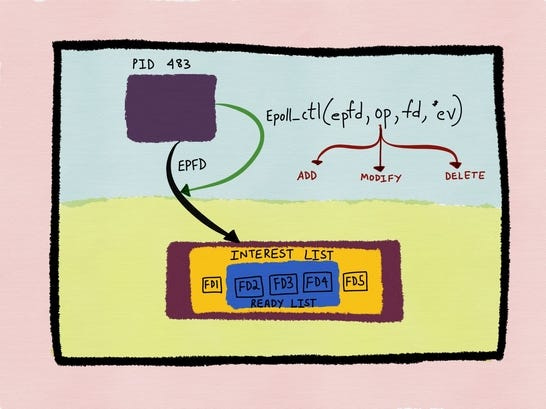

— Register fd with the epoll instance (EPOLL_CTL_ADD) and get notified about events that occur on fd

— Delete/deregister fd from the epoll instance. This would mean that the process would no longer get any notifications about events on that file descriptor (EPOLL_CTL_DEL). If a file descriptor has been added to multiple epoll instances, then closing it will remove it from all of the epoll interest lists to which it was added.

— Modify the events fd is monitoring (EPOLL_CTL_MOD)

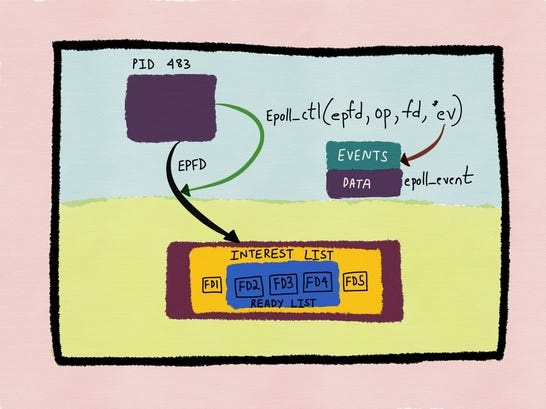

event — is a pointer to a structure called epoll_event which stores the event we actually want to monitor fd for.

Once registered, you wait:

epoll_wait(epfd, events, maxevents, timeout);Here, the calling thread sleeps until the kernel has events ready. Instead of scanning all registered file descriptors, the kernel returns only those whose state has changed. If nothing is happening, this call is cheap. If many things happen at once, the cost is proportional to the number of active events—not the total number of connections.

The crucial difference is that epoll_wait does not scan all file descriptors. The kernel already knows which ones are ready and returns only those.

𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐛𝐮𝐢𝐥𝐝 𝐆𝐢𝐭, 𝐃𝐨𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐫, 𝐑𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐬, 𝐇𝐓𝐓𝐏 𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐜𝐡. Get 40% OFF CodeCrafters: https://app.codecrafters.io/join?via=the-coding-gopher

Level-triggered vs edge-triggered behavior

epoll supports two modes that shape how events are delivered.

In level-triggered mode, an event is reported as long as the condition holds. If a socket is readable and you don’t drain it fully, epoll will keep notifying you.

In edge-triggered mode, epoll only notifies you when the state changes—from not-ready to ready. If you miss the event and don’t read all available data, you may never be notified again.

Edge-triggered mode can be more efficient but requires careful, non-blocking code. Many subtle bugs live here.

This flexibility makes epoll powerful—but also sharp.

kqueue: a more general event system

On BSD systems (including macOS), the equivalent mechanism is kqueue.

At a glance, kqueue looks similar: you create a kernel event queue, register interests, and wait for notifications.

int kq = kqueue();

kevent(kq, &change, 1, NULL, 0, NULL);The first call creates a kernel-managed event queue. The second registers a change request—an instruction telling the kernel what kind of event you care about, such as socket readability, a signal, or a file change. Like epoll, this registration persists until you remove it.

But kqueue goes further. It’s not just about file descriptors.

kqueue can monitor:

file changes

process lifecycle events

signals

timers

sockets

All through the same interface.

Where epoll is specialized and minimal, kqueue is general and expressive. It treats “events” as first-class citizens, not just I/O readiness.

Push vs pull: the real distinction

The most important shift epoll and kqueue introduce is philosophical.

With select and poll, user space repeatedly pulls state from the kernel. With epoll and kqueue, the kernel pushes events to user space when something interesting happens.

This inversion changes the cost model entirely. Idle connections are cheap. Active connections drive work. Scale becomes feasible.

How Go uses epoll and kqueue

Go’s runtime builds its network scheduler directly on top of epoll and kqueue.

When you write:

conn.Read(buf)From your code’s perspective, this is a blocking call. The goroutine stops executing until data arrives.

Under the hood, Go sets the socket to non-blocking mode, registers it with epoll or kqueue, and parks the goroutine. No OS thread is blocked waiting for data. When the kernel signals that the socket is ready, the runtime wakes the goroutine and resumes execution exactly where it left off.

This is how Go achieves massive concurrency without exposing async complexity to user code.

Why this model won

epoll and kqueue didn’t just improve performance—they changed how systems are designed.

They made it practical to:

handle tens of thousands of connections

multiplex I/O onto a small thread pool

build event-driven runtimes without callbacks

separate logical concurrency from physical threads

Almost every modern high-performance server relies on these ideas, directly or indirectly.

Final thought

epoll and kqueue are not just APIs. They are acknowledgments that waiting is the dominant cost in networked systems—and that waiting must be handled efficiently.

By moving bookkeeping into the kernel and shifting from polling to notification, they turned idle time from a liability into something close to free.

Most developers never call epoll or kqueue directly.

They still benefit from them every day.

another great read!! 🤭