Understanding Foreign Function Interfaces

Where Languages Touch

Introduction

“Abstraction is powerful, but performance lives in the details.” — Bjarne Stroustrup

At some point, most serious systems outgrow a single language. You may need a fast numeric library written in C, a legacy system that cannot be rewritten, or direct access to operating system APIs that your language runtime does not expose. A Foreign Function Interface, or FFI, is the mechanism that allows code written in one language to call code written in another. This capability is foundational to modern software stacks, even when it remains mostly invisible.

What an FFI Is

An FFI is a boundary-crossing mechanism. It defines how values are passed, how functions are called, how memory is shared, and how errors are handled when control moves from one language runtime into another. At its core, an FFI exists because compiled code ultimately follows machine-level calling conventions. If two languages agree on how arguments are laid out in memory and how control transfers, they can interoperate.

What makes FFIs challenging is not the call itself but the mismatch between language models. Different languages manage memory differently, represent data differently, and make different assumptions about ownership and lifetime. The FFI is where those assumptions collide.

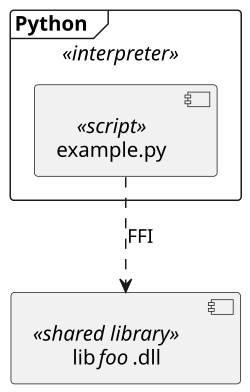

An FFI (Foreign Function Interface) is essentially a bridge that lets code written in one programming language (like Python) call a function written in another language (like C or Rust).

Different languages use the same rules. While Python and C look very different to a human programmer, the final machine instructions they generate for a particular operating system (like Windows or Linux) must both obey that OS’s specific machine-level calling conventions.

UML diagram example of an Python script running inside the Python interpreter and calling a shared library though FFI.

Why FFIs Exist

Many languages deliberately trade low-level control for safety and productivity. Others trade safety for performance or system access. FFIs allow developers to mix these strengths. A high-level language can orchestrate logic and concurrency while delegating performance-critical or system-facing work to a lower level language.

This is why operating systems, databases, cryptography libraries, and machine learning frameworks almost always expose C-compatible interfaces. C acts as a common denominator that many runtimes can speak through FFIs.

Calling Into C from Go

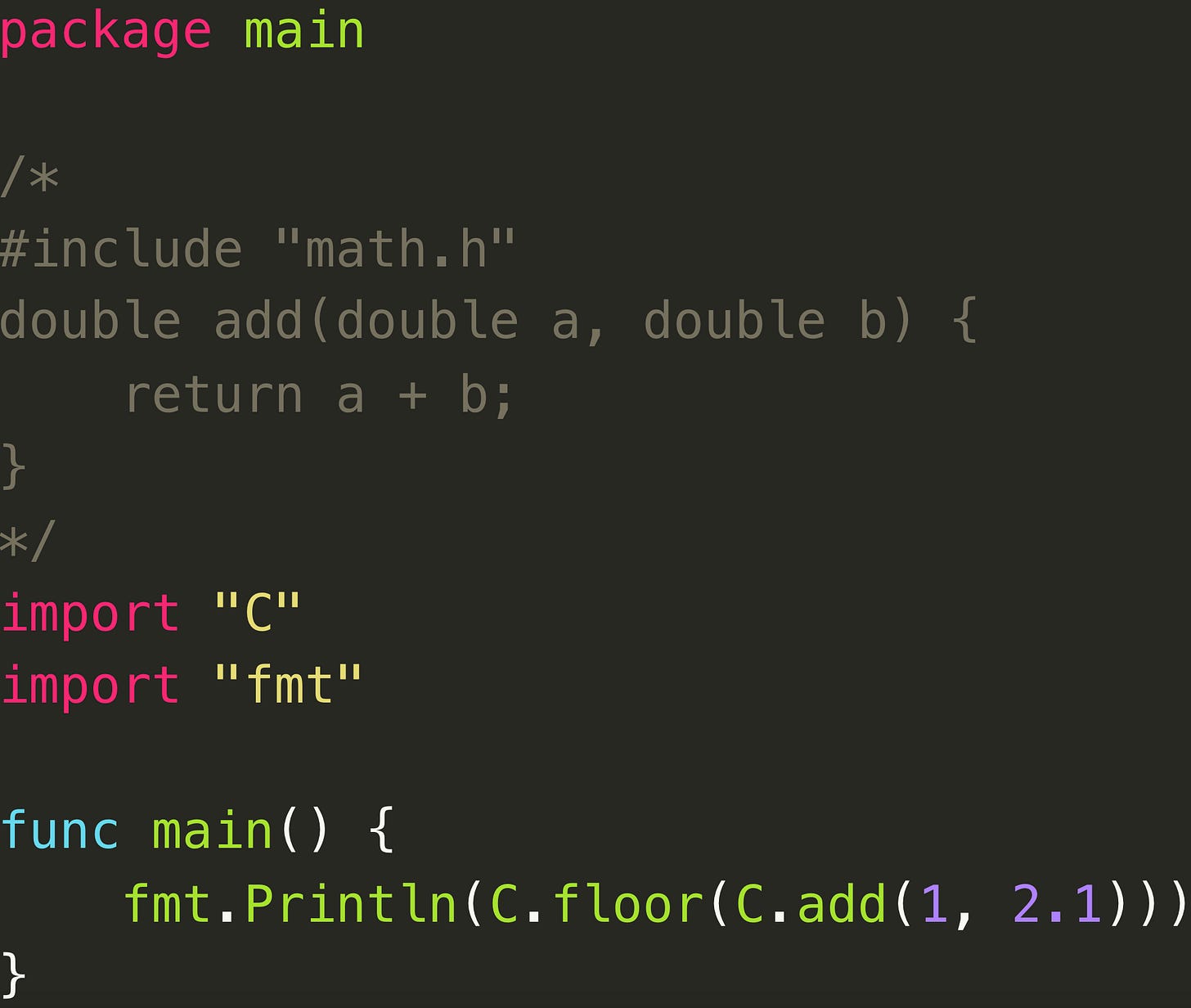

Cgo is the Go tool and mechanism that enables Go programs to call C code, and vice versa. It acts as a foreign function interface (FFI), bridging the gap between the two languages so developers can leverage existing C libraries and access low-level system functionalities that may not be available in Go’s standard library.

Consider a simple C function that adds two integers.

/* add.c */

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}Now call this function from Go.

package main

/*

int add(int a, int b);

*/

import “C”

import “fmt”

func main() {

result := C.add(2, 3)

fmt.Println(result)

}Here, the Go compiler coordinates with a C compiler. The Go runtime knows how to call the C function using the correct calling convention. From the developer’s perspective, it looks like a normal function call, but under the hood the runtime must switch execution contexts and obey C ABI* rules.

Concepts

import “C”: This is a special, pseudo-package that tells the Go toolchain to enable cgo for that file. It is not a real package you can find on disk.Preamble: Any C code (including

#includestatements, function declarations, and definitions) placed in a multi-line comment immediately before theimport “C”line is considered the cgo preamble. This code is compiled separately by a C compiler (like GCC or Clang) and linked with the Go program.Type Mapping: Cgo handles the translation of data types between Go and C. It provides special functions like

C.CString()(Go string to C string),C.GoString()(C string to Go string), and C type names likeC.intorC.size_tfor explicit conversions.Memory Management: This is a crucial difference. Go uses garbage collection for its memory, while C memory must be managed manually using

C.mallocandC.free. It is the developer’s responsibility to free C-allocated memory to prevent leaks.

Use Cases and Considerations

Cgo is typically used for:

Interfacing with existing, highly optimized C/C++ libraries (e.g., for graphics, cryptography, or database connectors like OpenSSL).

Interacting with low-level operating system APIs (e.g., POSIX functions).

Performance-critical code sections that are already highly optimized in C.

However, using cgo introduces complexities and trade-offs:

Performance Overhead: Calls between Go and C involve a context switch and data marshaling, which adds overhead compared to native Go function calls.

Memory Safety: Cgo bypasses Go’s memory safety guarantees. Bugs in C code can crash the entire Go program.

Concurrency Issues: Mixing Go’s goroutines and C threads can lead to issues if not managed carefully (e.g., using

syncprimitives orruntime.LockOSThread()).Cross-Compilation Difficulty: Pure Go code is easy to cross-compile, but cgo requires the presence of a C cross-compiler for the target architecture, making the build process more complex.

Overall, while powerful, cgo adds complexity and is generally recommended for specific scenarios where leveraging existing C code is necessary, rather than for general greenfield development.

ABI (Application Binary Interface) is a low-level specification defining how compiled software components (like libraries and the OS) talk to each other at the machine code level, standardizing data types, function calls (parameters, return values, registers used), and memory layout to ensure compatibility, even across different compilers or languages. It’s the contract for pre-compiled code, distinct from an API (Application Programming Interface) which governs source code interactions.

API (Application Programming Interface): A high-level, source-code level interface (e.g., C headers).

ABI (Application Binary Interface): A low-level, binary-level interface (e.g., machine code instructions).

𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐛𝐮𝐢𝐥𝐝 𝐆𝐢𝐭, 𝐃𝐨𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐫, 𝐑𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐬, 𝐇𝐓𝐓𝐏 𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐜𝐡. Get 40% OFF CodeCrafters: https://app.codecrafters.io/join?via=the-coding-gopher

Data Representation and Memory Ownership

“The hardest part of FFI is not calling functions; it is ensuring the memory they use still exists when they return.”

When you mix languages, you mix memory models. Languages like Go, Python, Java, and C# rely on a Garbage Collector (GC) to manage memory automatically. C and Rust rely on Manual Management (or ownership rules).

When a pointer crosses the FFI boundary, these two worlds collide. If ownership is not explicitly defined, you get crashes, leaks, or data corruption.

The Core Conflict: Movers vs. Stayers

The fundamental issue is that Garbage Collectors are active managers.

Reclaiming: The GC frees memory it thinks is unused.

Compacting: Some GCs (like in Java or Go) move objects around in RAM to defragment memory.

C assumes that if it has a pointer to an address (e.g., 0x00FF), the data at that address will be there forever until explicitly freed. If the GC moves that object behind C’s back, C is now pointing to garbage.

Scenario 1: Passing Managed Memory to C (Outbound)

You create an object in Go/Python and pass it to a C function.

The Risk: The GC sees that your Go code is done with the variable and reclaims it, not realizing that C is still holding a pointer to it. Or, the GC moves the object to a new address, invalidating the pointer C holds.

The Fix: Pinning

To do this safely, you must “Pin” the memory.

Pin: You tell the Runtime, “Do not move or collect this object, even if it looks unused.”

Call: You pass the pointer to C.

Unpin: Once C returns, you notify the Runtime that the object is safe to manage again.

Note: Pinning reduces the GC’s efficiency because it fragments memory, so it should be minimized.

Scenario 2: C Allocating Memory for the Host (Inbound)

C mallocs a buffer and returns a pointer to Go/Python.

The Risk: The Host Language (Go/Python) receives a pointer, but its GC has no idea how much memory that pointer represents or who owns it.

The Leak: When the Host object dies, the GC destroys the pointer, but it does not call

free(). The massive data buffer allocated by C remains in RAM forever (Memory Leak).

The Fix: Manual Finalizers

You must manually bridge the gap.

Explicit Free: You expose a

free_result()function in your C API and call it manually from the Host.Finalizers: In Python/Java, you can attach a “Finalizer” or “Destructor” to the object wrapper that calls

free()in C when the GC collects the wrapper.

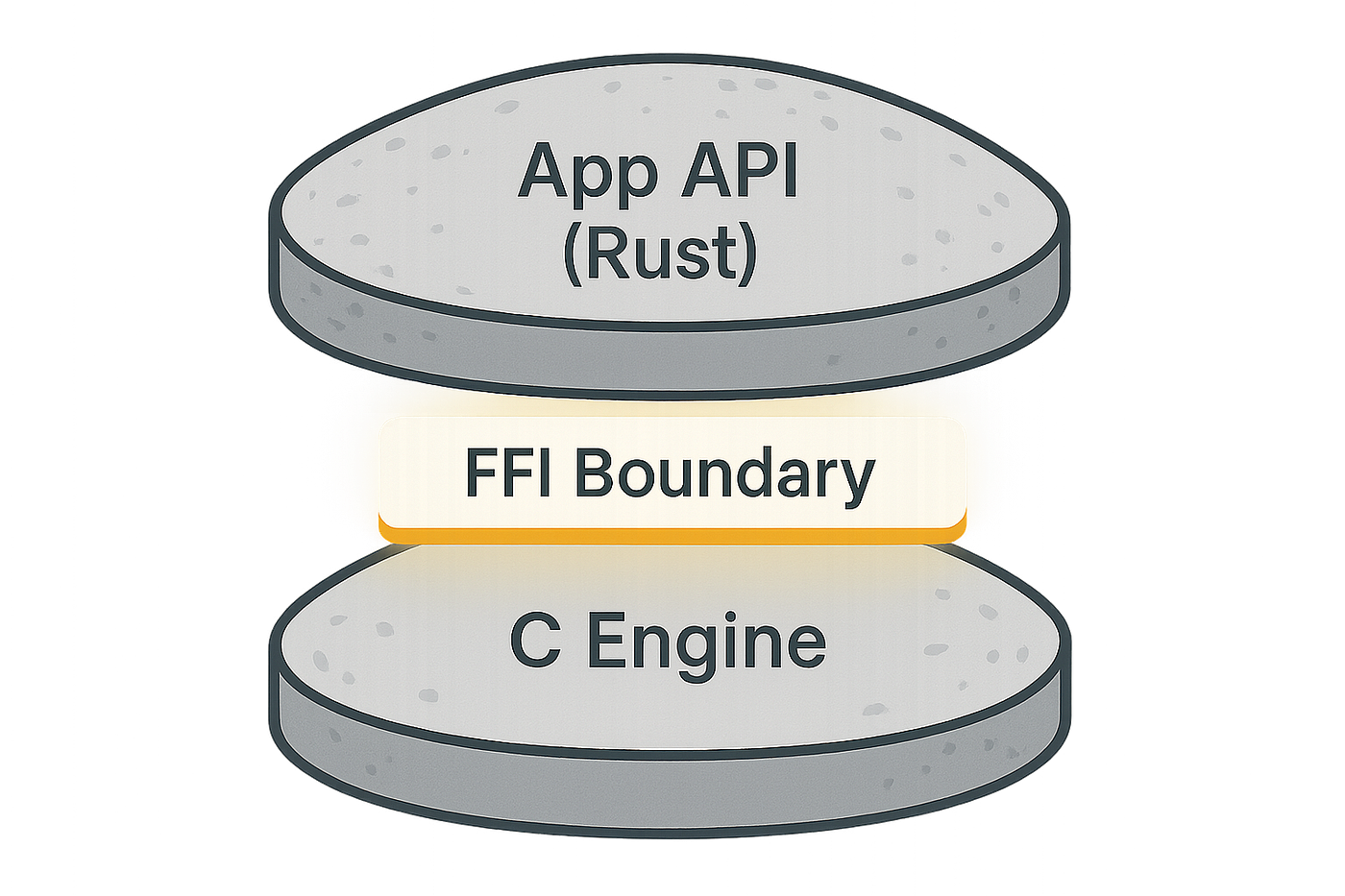

Summary. The Cost of Safety

FFIs impose strict rules because the compiler’s safety guarantees stop at the border.

Go requires strict checks (cgo rules) to ensure you don’t pass Go pointers to C incorrectly.

Rust forces you to mark FFI blocks as

unsafe, acknowledging that the compiler can no longer protect you.

FFI Call Overhead

FFI calls are more expensive than native function calls. The runtime may need to marshal arguments, convert data layouts, pin memory, and transition into a different execution model. In garbage-collected languages, the runtime may also need to coordinate with the collector to ensure safety.

This overhead usually does not matter for coarse-grained calls. It becomes important when FFIs are used inside tight loops. In those cases, the cost of crossing the boundary can dominate execution time.

Error Handling Across Boundaries

Error handling rarely maps cleanly across languages. C uses return codes. Go uses multiple return values. Python uses exceptions. When calling across an FFI, errors must be translated into a form the caller understands.

This translation often loses information. Stack traces may not cross the boundary. Exceptions may become integers. Subtle bugs can arise when error semantics are misunderstood. Good FFI design keeps error handling simple and explicit.

Safety and Undefined Behavior

Using a Foreign Function Interface (FFI) is like opening a wormhole in your code. You gain speed and access to new worlds, but you bypass the physics (safety rules) of your home universe.

1. The Compiler’s Blind Spot

Modern languages rely on their compilers or interpreters to enforce rules—checking for uninitialized variables, tracking object lifetimes, or preventing data races.

The Problem: When you call a C function from Python (or Rust, or Go), the host language sees a “black box.” It cannot see inside the function to check if it respects memory safety. It hands over control and simply hopes the foreign code behaves.

Aliasing & Lifetimes: The compiler cannot track pointers once they cross the boundary. It cannot guarantee that the C code won’t free a piece of memory that Python is still trying to read.

2. The Crash Radius

In managed languages, a bug usually results in an Exception (a traceback you can catch). In FFI land, a bug results in a Segmentation Fault.

Process Termination: A bad pointer doesn’t just crash the current thread or request; it crashes the entire operating system process.

Memory Corruption: Even worse than a crash is silent corruption. A C extension might accidentally write to the wrong memory address, corrupting a completely unrelated Python object. You might see a strange error 500 lines of code later, making debugging a nightmare.

3. The Containment Strategy: Safe Wrappers

Because of these risks, the “Golden Rule” of FFI is containment.

The Unsafe Core: You write the raw, dangerous C interactions in a small, isolated core.

The Safe Shell: You wrap this core immediately in a layer of defensive code (the “Safe Layer”). This layer checks inputs, validates buffer sizes, and ensures pointers are valid before passing them to C.

The Benefit: The rest of your application interacts only with the safe wrapper, treating the foreign code as a powerful but dangerous beast kept in a cage.

FFIs in Real Systems

Many systems you use daily depend heavily on FFIs. Python numerical libraries call C and C++ code. Databases expose C interfaces used by multiple languages. Operating systems export system calls through ABI-stable boundaries. Even language runtimes themselves are often written partly in C.

FFIs are not a niche feature. They are a core technique for composing software across decades of tooling and design decisions.

Why Understanding FFIs Matters

Understanding FFIs sharpens your mental model of how languages actually run. It forces you to think about memory layout, calling conventions, and ownership in concrete terms. It also explains why some abstractions have sharp edges and why performance sometimes drops unexpectedly at language boundaries.

Once you understand FFIs, many design decisions in runtimes and libraries make more sense. You see where safety ends, where responsibility shifts to the programmer, and why certain interfaces look the way they do.

amazing way to start off the year 🥂