Understanding the Python Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

One Thread to Rule Them All

Introduction

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” — Yogi Berra

Anyone who spends time writing concurrent Python eventually runs into the same question. If modern machines have many cores, why does Python not scale CPU-heavy code across them automatically? The answer is the Global Interpreter Lock, commonly called the GIL. The GIL is one of the most misunderstood parts of Python. It is neither a mistake nor a temporary hack. It is a deliberate design choice with deep consequences for performance, safety, and simplicity.

The Basics

Processes are isolated from one another in distinct memory areas. This design provides fault tolerance: a crash in one process generally will not bring down the entire system or affect peer processes.

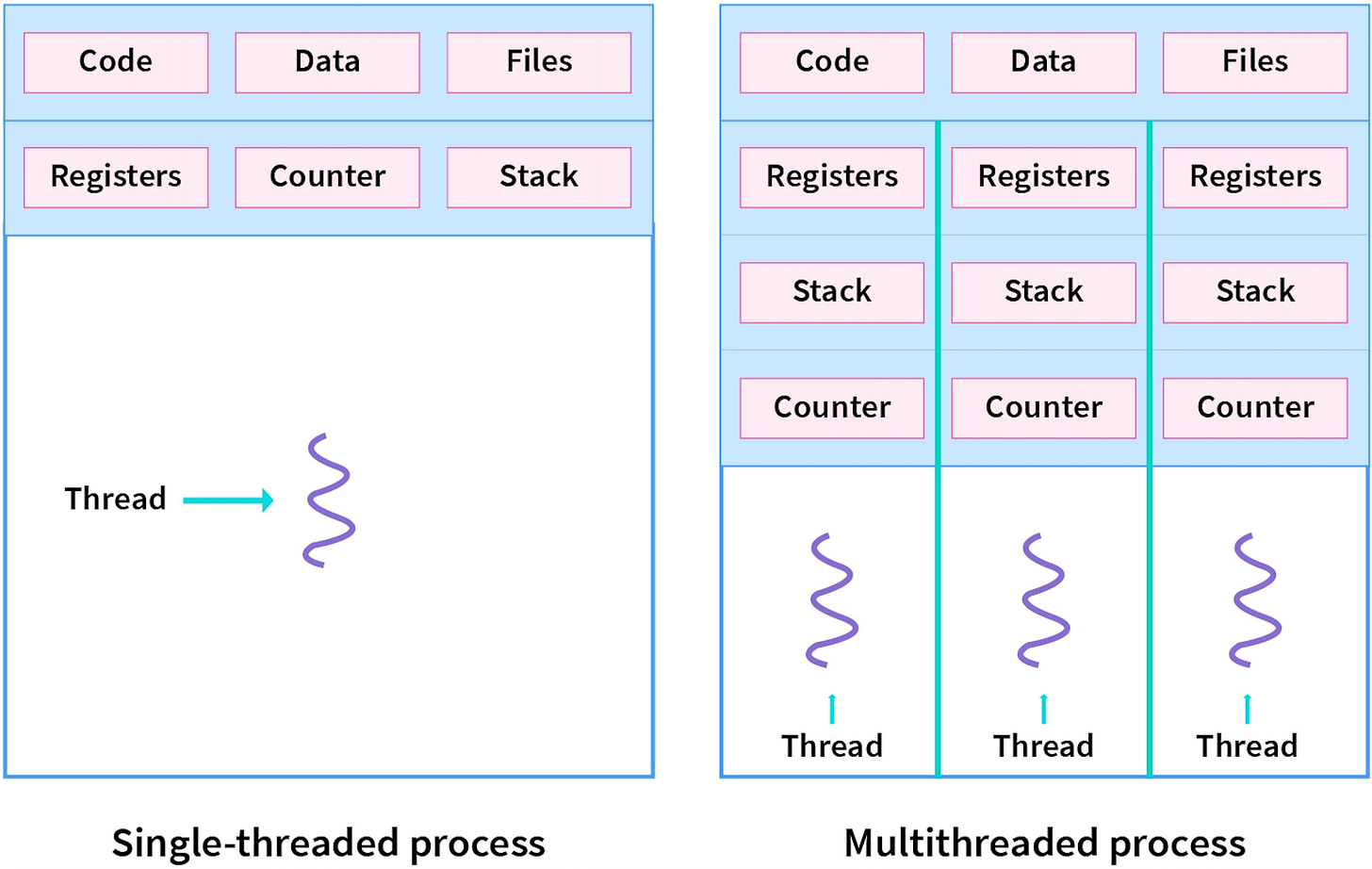

A thread is the smallest unit of execution that can be scheduled, essentially a lightweight sub-process that runs within a larger process, sharing its memory and resources but having its own program counter, stack, and registers.

Multithreading involves a single program (process) running several simultaneous streams of execution (threads), all of which share the same allocated resources, such as memory space.

What the GIL Is

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) is a mutex in CPython (the standard Python interpreter) that allows only one native thread to execute Python bytecode at a time, even on multi-core processors, preventing true parallel execution for CPU-bound tasks but simplifying memory management. It’s a performance bottleneck for parallel computation but less impactful for I/O-bound tasks, where threads wait. Developers bypass it for CPU-heavy parallelism using separate processes (multiprocessing) or different Python implementations (Jython, IronPython).

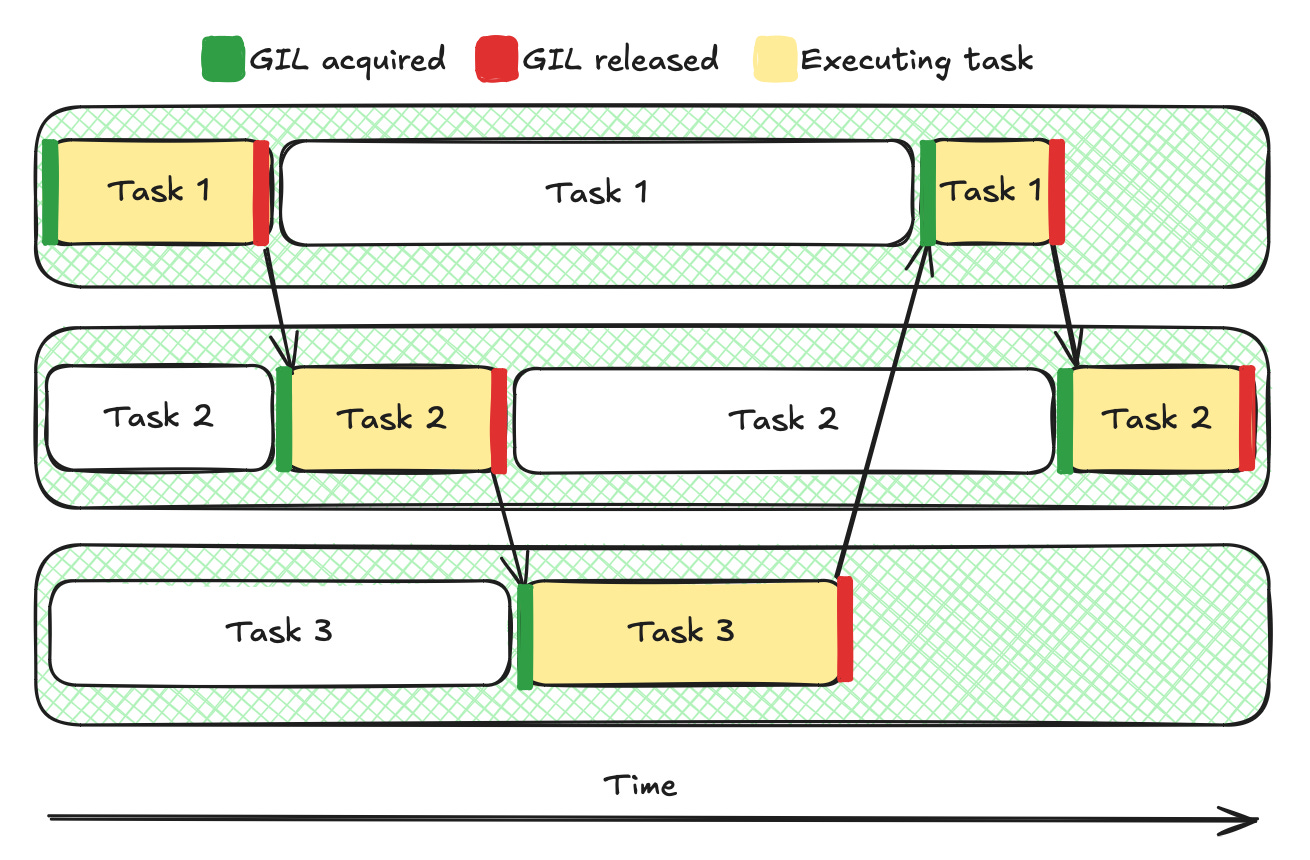

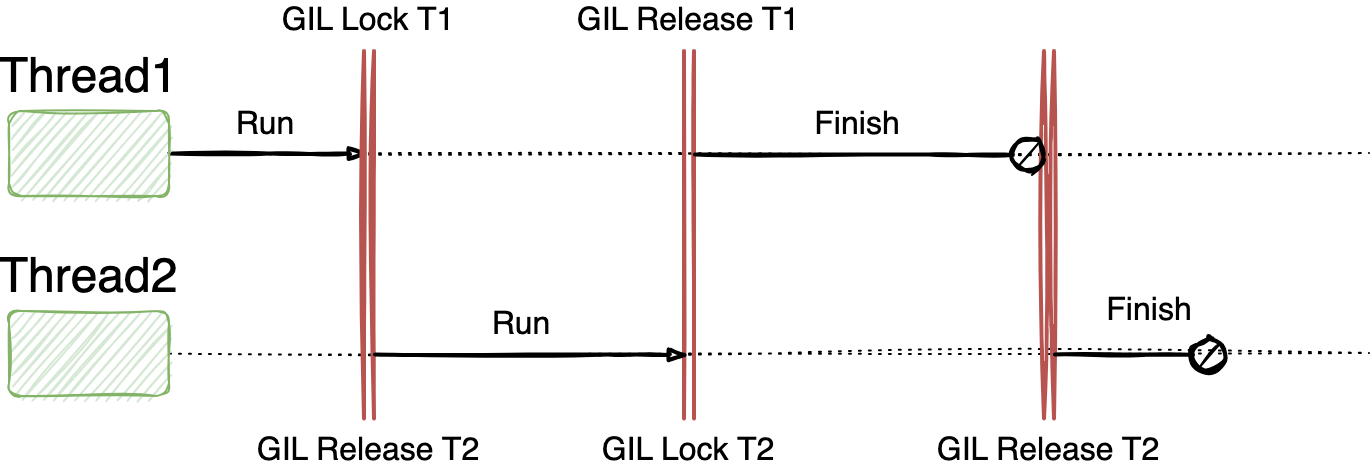

This does not mean Python cannot use threads. It means Python threads take turns executing. The interpreter periodically switches between them, giving the illusion of parallelism while enforcing a single point of execution for Python bytecode.

Schematic representation of how threads work under GIL. Green - thread holding GIL, red - blocked threads

Why the GIL Exists

The primary reason for the GIL is memory safety. Python uses reference counting to manage object lifetimes. Every object tracks how many references point to it. Updating reference counts happens constantly and must be correct at all times.

Without the GIL, every reference count update would require fine-grained locking. That would significantly slow down single-threaded code and make the interpreter far more complex. The GIL trades parallel execution for simpler and faster object management in the common case.

What the GIL Protects

The GIL protects internal interpreter state, acting as a single global lock that ensures only one thread can execute Python bytecode at a time. This protected state includes:

Reference Counts: The core mechanism for memory management in Python, ensuring objects are deallocated correctly when no longer in use.

Memory Allocators: Structures managing how and where memory is assigned for Python objects.

Garbage Collection Structures: Data used by the generational garbage collector to find and clean up unreachable objects.

The primary consequence of the GIL is that most operations within the Python C API are inherently thread-safe without requiring additional explicit locking mechanisms. This design choice simplifies development for C extension authors, who can reliably assume the interpreter state remains consistent and will not be modified concurrently by another thread, unless they consciously and explicitly release the lock for specific operations (such as blocking I/O or long-running computations).

Threads With the GIL

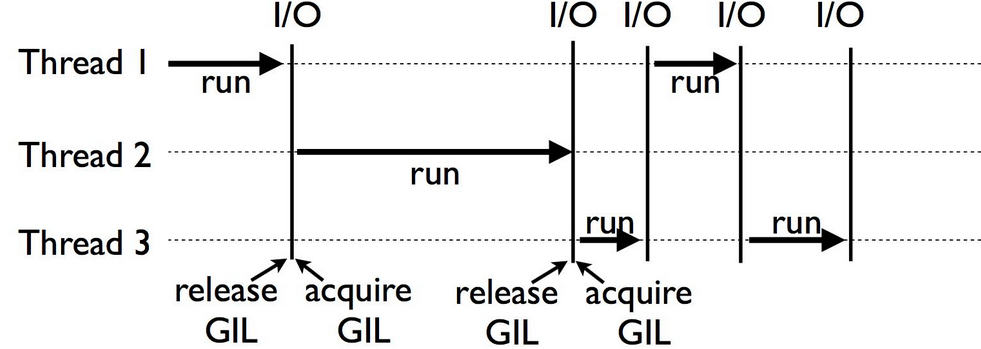

Python threads are real operating system threads. They can block independently on system calls such as network reads or disk access. When a thread blocks on input or output, it releases the GIL so another thread can run.

This is why Python threads work well for input and output-bound workloads. While one thread waits, another can make progress.

import threading

import time

def worker(name):

print(name, “starting”)

time.sleep(1)

print(name, “done”)

threads = []

for i in range(3):

t = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=(i,))

t.start()

threads.append(t)

for t in threads:

t.join()All threads overlap in time because sleeping releases the GIL. The program finishes in roughly one second, not three.

CPU-Bound Code and the GIL

CPU-heavy Python code does not scale across cores because the GIL prevents simultaneous execution of bytecode. Threads must take turns even if multiple cores are available.

import threading

def count():

x = 0

for _ in range(10_000_000):

x += 1

threads = [threading.Thread(target=count) for _ in range(2)]

for t in threads:

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()This program does not run twice as fast on a two core machine. Both threads compete for the GIL and execute sequentially.

Releasing the GIL in C Extensions

C extensions can release the GIL explicitly when performing long-running native computation. While the GIL is released, other Python threads may run.

This is how numeric libraries achieve parallelism. The heavy computation happens in C without holding the GIL. When the result is ready, the extension reacquires the lock before returning control to Python.

This design allows Python to combine safe object handling with parallel native execution.

Multiprocessing as an Alternative

Python supports multithreading through its built-in threading and concurrent.futures modules. However, in the standard CPython interpreter, the GIL limits a process to executing only one Python thread at a time (even on multi-core machines).

To bypass the GIL entirely, Python provides multiprocessing. Each process has its own interpreter and its own GIL. This allows true parallel execution across cores.

The cost is higher overhead. Processes do not share memory easily. Data must be serialized and passed between processes. This tradeoff is often acceptable for CPU-heavy workloads.

Common Misconceptions

The GIL does not prevent concurrency. It prevents parallel execution of Python bytecode. Input and output operations still overlap. Native extensions can still run in parallel. Multiple processes can still scale across cores.

The GIL is also not a global lock across the entire system. It only exists within a single Python process.

Why the GIL Still Exists

Removing the GIL would require fundamental changes to Python’s memory model and C extension ecosystem. Many extensions rely on GIL guarantees. Removing it would likely slow down single-threaded programs and break compatibility.

For these reasons, the GIL remains part of CPython. Other Python implementations explore different tradeoffs, but CPython prioritizes simplicity, stability, and performance for the majority of use cases.

No-GIL Python?

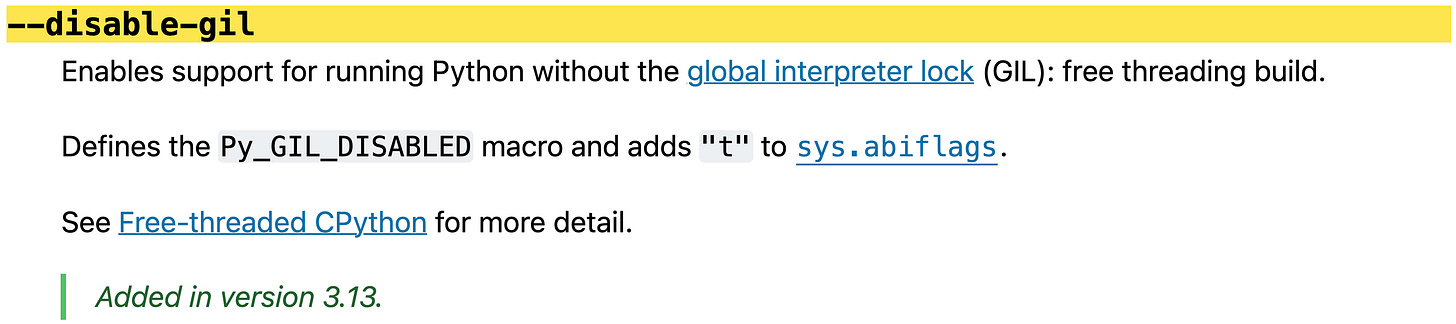

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) is not fully gone, but it is now an optional feature to disable in recent Python versions (like 3.13/3.14) through specific builds, allowing true multi-core parallelism for CPU-bound tasks, though it requires careful use as it is experimental and not in default installations yet. It is a gradual, experimental process (PEP 703) to make Python faster, with the hope of a fully free-threaded version in the future, but default builds still have it.

Why Understanding the GIL Matters

Understanding the GIL changes how you design Python programs. It clarifies when threads help and when they do not. It explains why input and output workloads scale well and why CPU-heavy workloads do not. Once you understand the GIL, performance behavior stops being surprising. You choose threads, processes, or native extensions intentionally, based on what your program is actually doing.

loving the python content!!! happy new year gopher :))